By funkhaus

Throughout Massachusetts and beyond, housing density, zoning for housing, and transit-oriented development are hot topics of conversation for many communities. Project Manager and Marketing + Community Liaison Sophie Nahrmann offers context around these topics, advocates for a shared definition of density, and explains the benefits transit-oriented developments can hold for communities in the Greater Boston Area.

Why is housing density such a debated issue?

While some districts and communities seek housing density to promote economic revitalization and a host of other progressive goals, the changes associated with it are also feared. I think people often hear density and they think of an ugly high rise — they think of more and bigger buildings, more asphalt and concrete, fewer trees and green space, less sunlight and privacy.

As architects, we would argue that density can be designed to be beautiful and thoughtful, and has benefits which include more efficient land use and energy efficiency. You can preserve more open space, and you can design more energy-efficient buildings than what single family housing zoning would allow. This is all in line with what we’re thinking about as we are looking at global climate change and updated building code requirements for building performance as well. Looking at how increased density can tie into that while also being aligned with the needs and wants of different communities in Massachusetts is important.

What exactly does density mean in this context?

In particular when thinking about things like 3A laws and state requirements for development in transit-oriented areas — or areas that are served by public transit like the commuter rail or the MBTA stops in Boston — that are being debated in Massachusetts right now, there are some misconceptions about what the proposed density means. The laws allow municipalities to retain extensive local control to determine things like the shape and form of what is allowable, and the required density in these zones is usually quite modest. Think triple-deckers or, for a few communities, small apartment buildings, not high rises. Each town has the flexibility and agency to size the zoning changes to what’s appropriate for their communities, how many commuters are actually coming into and out of the city, and what their transit usage is for the city. Everyone has a different idea of what density means, so agreeing upon a common definition of density is helpful in having that conversation, and allows us to contextualize what it looks like.

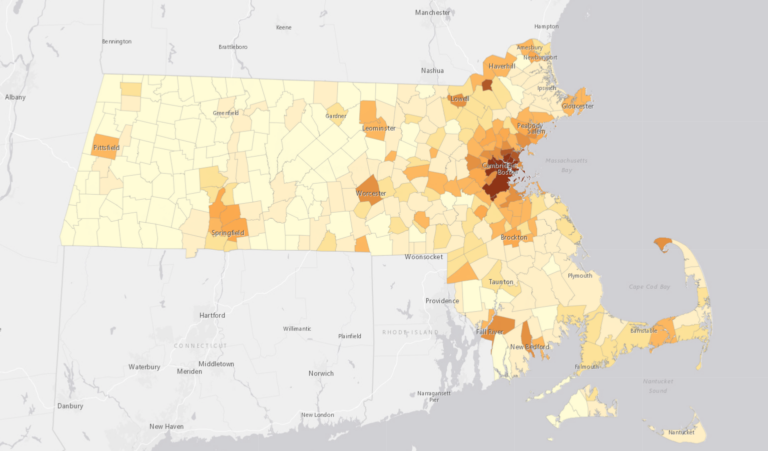

MHP’s Residensity tool helps people and towns visually understand their existing density.

How does housing density intersect with issues like race and class, both historically and currently?

Massachusetts has an extensive history of using racial covenants and exclusionary zoning policies to keep people of color out of certain communities — for more on this, we recommend reading Researcher Amy Dain’s comprehensive investigation. Multifamily housing tends to serve Black and brown communities, low-income people, and younger populations, while wealthy cities and towns, composed of majority homeowners with high property values, are often wary of the impacts that an influx of renters and lower income households will have on their towns. Historically, by using zoning to limit development on one-acre lots to single-family homes, for instance, towns catered to the most affluent buyers, which in this case is the state’s white demographic. If we continue that type of zoning, then what we have is a permutation of exclusionary zoning practices — essentially de facto legalized segregation. State Attorney General Andrea Campell and Civil Rights groups have warned suburbs against preserving zoning laws that perpetuate racial segregation across the region, and MBTA Communities that fail to comply with the Law’s requirements also risk liability under federal and state fair housing laws.

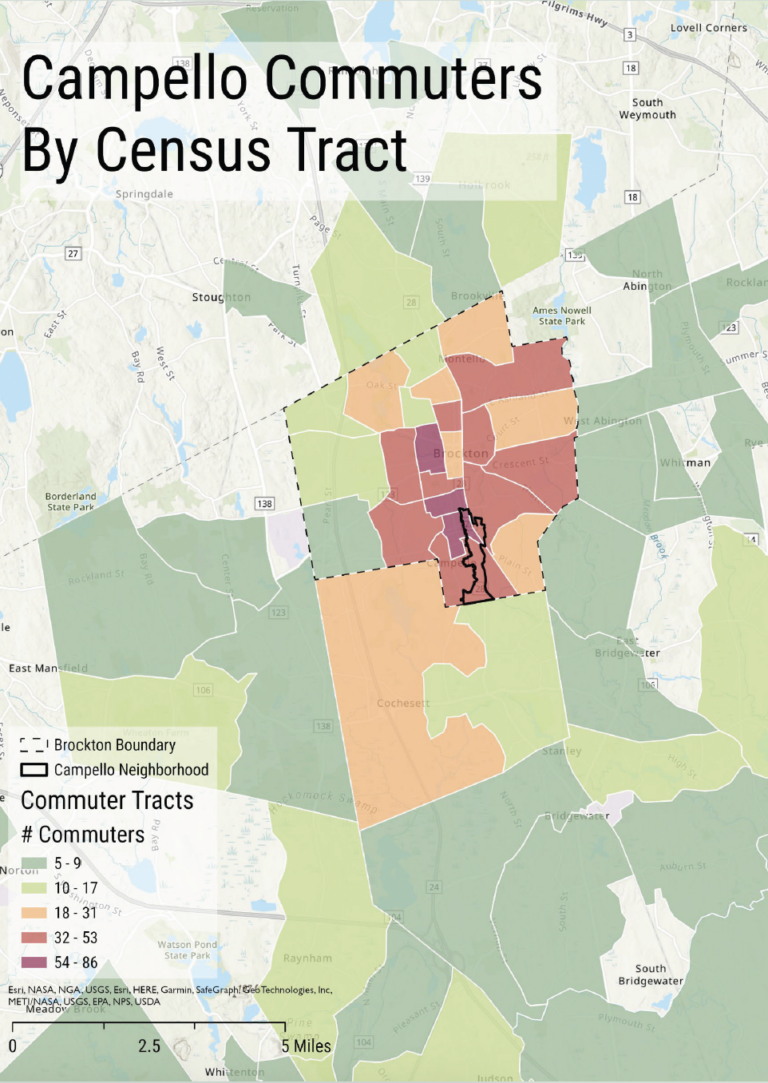

This map of Brockton, with Campello designated by a solid boundary, shows the number of commuters in each of the area’s tracts.

As far as transportation, what are some concerns as it relates to density?

A common concern is that the transportation system is already struggling to meet service expectations and some suggest that planning for increased development that relies on that system may not have the desired effect, ultimately relying on cars to overcome the system challenges. However, building housing in transit-oriented neighborhoods increases opportunities for multimodal transit, which limits dependence on individual car ownership and reduces traffic, something that is important especially in high-congestion cities like Boston. You then have opportunities for better pedestrian and bike connections and other transit, instead of relying on the single family housing model, with multiple cars for a single household.

This ultimately results in reduced vehicle miles traveled and less greenhouse gas emissions. Households living near transit tend to own fewer cars and drive less than households who lack transit access, even after controlling for income, neighborhood density, and other factors. This approach can also start to improve green infrastructure and preserve a lot of open space by reducing sprawl and minimizing land consumption. There’s some studies that anticipate that putting 60% of the new housing near transit would preserve 115,000 acres of land. I think that preserving green open space is interesting to factor in when you think about the benefits density can provide.

We recommended creating a dedicated area for new multi-unit housing right by the Campello MBTA commuter rail station as part of our work on Brockton’s Campello Neighborhood Plan.

What benefits can mixed-used, multi-family, higher density housing offer for towns?

Increased density in transit-oriented neighborhoods results in more options for housing. The state of Massachusetts has a huge lack of housing units — it’s estimated that we need 200,000 more housing units in the state in the next six years. People are competing for limited stock and are often getting priced out, and as a result, we’re losing a lot of our workforce as people move to more affordable areas. Keeping people in their communities is important in terms of retaining diversity in our neighborhoods, as well as promoting economic growth. Based on current development proposals, existing land use, and redevelopment opportunities, some studies estimate that transit station areas could accommodate more than 76,000 new housing units and space for more than 130,000 new jobs by 2035, which would do a significant job at addressing the state’s lack of housing units.

Our work on the Campello Neighborhood Plan for the City of Brockton exemplifies this. On this project, we worked towards aligning zoning recommendations with transit-oriented development recommendations, including creating a dedicated area for new multi-unit housing right by the Campello MBTA commuter rail station. Many people who are leaving Boston are moving to Brockton and places like it, so determining how people can remain connected to urban centers is something we’re thinking about, especially in older industrial towns like Brockton. Even within this small area of Campello, we prioritized increasing affordable housing, creating opportunities for new commercial zones, and improving the public space and the connections to that space.

This approach also means creating a stronger foundation for local businesses to thrive — our work with Shirley Ave in Revere, where we developed conceptual design schemes for three existing local businesses in shared spaces, is a good example. The initiatives in that area aim to retain and promote the diversity and the resulting vibrance and connection of those communities. Considering the retention of the existing community and businesses is important — the loss of the local businesses who are getting priced out of retail storefronts is a huge problem. Increasing density means a higher customer base and a better economic engine overall.

Our conceptual shared space designs for existing Shirley Ave businesses help preserve the area’s unique personality and diversity.

What about benefits for families and individuals?

The cost of living is a major burden to many Metro Boston households and a deterrent to attracting more workers to the region — the average household spends 28% of its income on housing and an additional 20% on transportation. However, households in transit station areas spend less of their income on transportation, especially if they can get by with one or zero vehicles instead of two. This increased accessibility and affordability is a huge benefit for families and individuals in these communities.

This approach also fosters greater physical activity as people walk to transit and nearby destinations, improving overall health. Safety is also generally up, as increased transit usage and less auto usage may also result in fewer car accidents and less air pollution as compared to other, more sprawling areas.